Global shortages of automotive semiconductors have forced car manufacturers to shut down assembly lines and mull supply chain resiliency strategies to prevent further disruptions over the long term. Now the Biden Administration, as part of its review of key U.S. supply chains, is also taking a close look at how the supply of semiconductors and chips can be ensured in the interest of American manufacturing industries in general.

Late last year, unanticipated demand for automotive semiconductors began chasing dwindling supplies of the specialized chips. As of this month, there is no sign of shortages easing and virtually every major carmaker is reported to have cut back vehicle production.

The underlying cause for the shortage is largely due to automakers in North America and Europe betting that demand for new cars would fall during the pandemic. Accordingly, they slashed orders for auto-grade chips starting March last year. In the face of cancelled orders, the chipmakers, who are concentrated in East Asia, shifted production to the pricier chips used in consumer electronics, demand for which was expected to surge (and did) as the pandemic forced people to work, school, and entertain themselves at home. Now, low interest rates, stimulus payments, and pent-up demand are bringing car buyers back to market. But with assembly lines stalled for want of chips, the number of vehicles on or en route to dealership lots dropped 10% between February and March, as the Wall Street Journal reports.

This is by no means the only supply chain bottleneck slowing the post-pandemic recovery. But its impact on the bellwether automotive industry – production cuts in 29 U.S. automotive assembly facilities in 13 states collectively employing over 100,000 workers, according to Autos Drive America – has raised the pressure on policymakers to take action.

Impact of COVID-19 and Semiconductor Shortages on U.S. Auto Trade

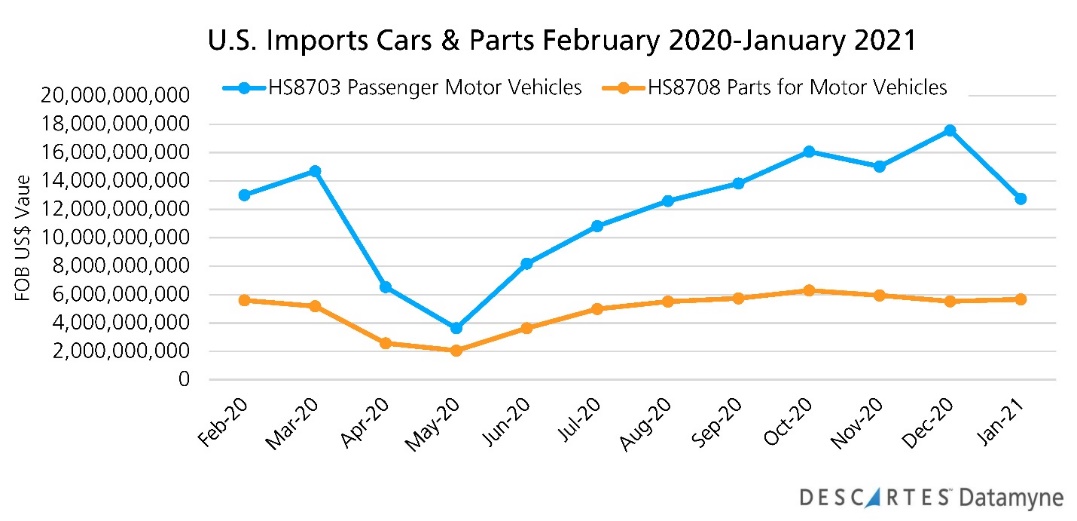

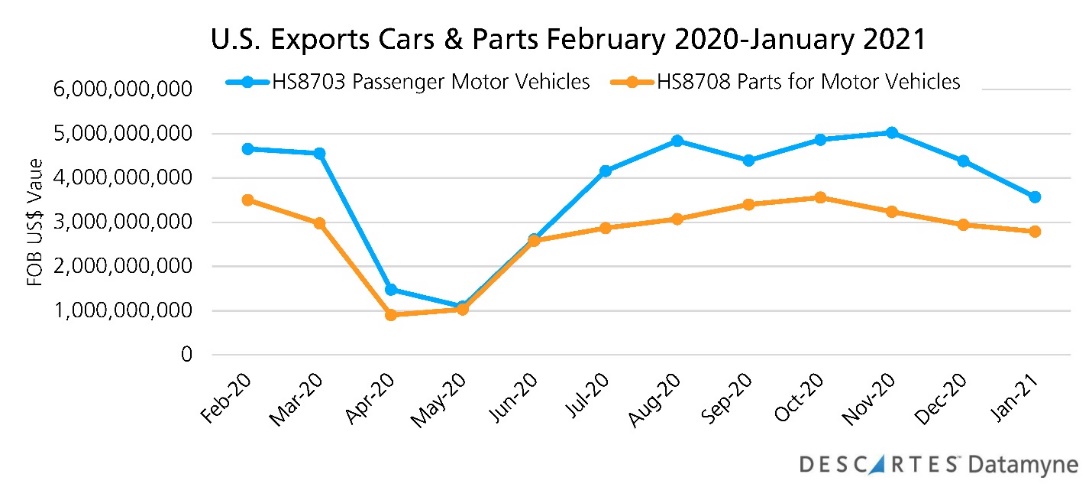

Here is the Descartes Datamyne research data on U.S. trade in cars and parts for motor vehicles. The charts show the fall and rise of trade aligning with the pandemic’s signature drop and recovery V-shaped trend line. For the 12-month period closing January 2021, exports of cars posted a y-o-y decline of 19.2% and parts were down 22.8%. Imports also posted losses: -17.3% for vehicles, -13.4% for parts.

What the U.S. Semiconductor Trade Data Shows

Descartes Datamyne data provides a broad view of U.S. commerce in semiconductors, revealing the U.S. as a net exporter by value of chips and chipmaking machinery.

The data through the 12 months ending in January 2021 for three Harmonized System tariff codes covering semiconductors or integrated circuits (HS8542), the devices that make up integrated circuits (HS8541), and the machines for making semiconductors (HS8486) is summarized here:

![]()

The data shows that the U.S. machinery for producing semiconductors (and the IP that goes with it) is bound for East Asian production hubs, as expected – although China’s leading share after years of U.S.-China trade tensions comes as a surprise.

![]()

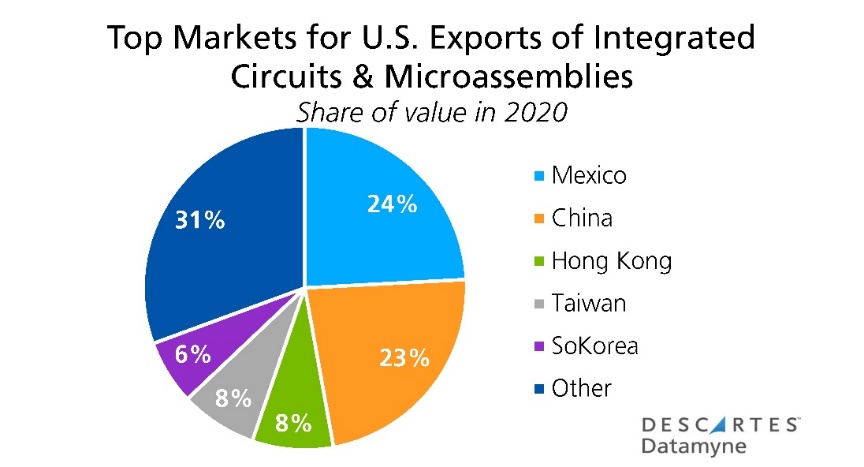

The list of top destinations for U.S. exports of integrated circuits and micro-assemblies last year is led by USMCA partner Mexico, edging out China as a point of product assembly by a percentage point:

The trade data on countries of origin for the diodes, transistors, and other devices that make up integrated circuits shows Southeast Asian countries stepping up to the global semiconductor value chain:

![]()

The trade data on U.S. semiconductor exports over the 12 months ending in January 2021 indicates a dip in shipments from April to May, in what appears to be a delayed response to pandemic disruptions. Overall, total U.S. exports of ICs for the 12 months increased 9.3% year-over-year, while chipmaking machinery exports surged 29.2%. Exports of diodes, transistors, etc., slipped 7.0%.

![]()

U.S. semiconductor imports in the year of COVID-19 dropped – precipitously in the case of ICs – following from March’s lockdowns (and automakers’ chip-order cancellations), as the next graph illustrates. Overall, imports of ICs closed the year ending January 2021 down 4.3%, while the machinery for making chips plummeted 21.9%. Imports of diodes, transistors and other semiconductor devices rose 9.4%

![]()

The lead-up to President Biden’s Executive Order to Review U.S. Supply Chain Resiliency

Among those calling for reshoring are the leaders of America’s semiconductor companies who sent President Biden a letter on February 11 to ask that his administration’s plans to “Build Back Better” include investment in domestic chipmaking. The Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), along with a broad coalition of downstream users of chips, on February 18 wrote to urge the president to work with Congress to fund the domestic manufacturing and research provisions for semiconductors included in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

Subsequently on February 24, President Joseph Biden issued an executive order (EO) directing various federal agencies to undertake a review of risks to supply chain resilience in four sectors vital to the economy, starting with semiconductors (The other three sectors to be studied are pharmaceuticals; rare earths; and high-capacity batteries). The EO tasks the Department of Commerce with identifying risks in the chips manufacturing and advanced packaging supply chains and coming back with policy recommendations in 100 days.

Regional Specialization in Chips Production

The policy changes Commerce returns in June will be closely watched for signs of the Biden administration’s strategic view of globalization.

As a study from the SIA, conducted with Boston Consulting Group and released earlier this month makes clear, the semiconductor industry is a global enterprise. Semiconductors are the world’s fourth most-traded product, behind crude oil, motor vehicles and parts, and refined oil. Taken as a whole, the industry is a model of regional specialization – and the dominant player is the U.S., the global leader in design and development of semiconductor intellectual property (IP), as well as the destination for 35% of the chips used in the world, as this chart from the SIA-BCG report illustrates:

![]()

Note that U.S. leadership in semiconductor IP carries over to the design of equipment to make the chips. As the chart shows, the hub of world production is East Asia – Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan, especially. China, the leading manufacturer of electronic devices, has in recent years launched several initiatives to build out its semiconductor manufacturing capacity (China’s push caused concern in Washington and motivated the inclusion of funding for the U.S. industry in the NDAA. Government incentives lower the costs of building a foundry in China 37% to 50% compared with the U.S.).

The SIA-BCG report credits the global system of regional specialization with economies that effectively lower the price of semiconductors worldwide by 35% to 65% than they would otherwise be. Conversely, a shift to fully “self-sufficient” localized or national supply chains would require substantial capital investment. For example, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s new factory in Taiwan, scheduled to come online in 2022, is reported to cost US$19.5 billion to build. Costs of this magnitude, incurred across several countries, would inevitably result in higher prices to end users.

While this system of specialization has served the industry and its consumers well, the SIA acknowledges its vulnerabilities. There more than are more than 50 points across the supply chain where one region commands more than 65% of global market share. The risk of supply disruptions from natural causes, market shifts or geopolitical tensions varies. The SIA cautions that, rather than attempting to reshore the entire supply chain, national policies should focus on addressing these potential bottlenecks diplomatically as well as with bricks and mortar.

Options to Strengthen Supply Chain Resiliency

Traditionally, there’s a post-holiday easing of trade in passenger vehicles, but it’s too soon to gauge the effects of a protracted auto-grade chips shortage. But given the seriousness of the situation, U.S. automakers are likely reviewing options to strengthen the resiliency of their supply chains through alternative sourcing strategies.

Such a review includes examining whether there was an over-reliance on one or a few nations for supplies of certain goods, how to spread risk by cultivating supply sources across more countries as long as landed cost analysis made sense. When looked at in this light, calculating the viability of reshoring certain parts of the supply chain becomes more precise.

In spreading the risk, companies need to be sure that they are aware of all the supply chain options available from around the world. Descartes Datamyne delivers powerful global trade intelligence solutions to help businesses uncover viable sources of supply–even those you might not be aware of–to help them adapt to regulatory and geo-political changes.

Other major due diligence steps include ensuring that landed cost calculations are accurate for the planning and selection of the best supply chain paths, and weeding out individuals and organizations deemed to be bad actors by governments and world bodies via screening against denied parties lists.

How Descartes Can Help

Descartes Datamyne delivers business intelligence with comprehensive, accurate, up-to-date, import and export information that help companies save significant time in identifying new suppliers, markets, customers, and sources of products.

Our multinational trade data assets can be used to trace global supply chains and our bill-of-lading trade data – with cross-references to company profiles and customs information – can help businesses identify and qualify new sources.