Descartes Datamyne trade data reveals the complexities facing the Biden Administration as it aims to strike a balance among three competing objectives: Accelerate the U.S. transition to clean energy, build out U.S. clean energy manufacturing capacity, and wean the U.S. from depending on China as a source of supply.

Case in point: The latest U.S. Section 301 tariffs on Chinese imports. On September12, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative issued its final determination on the proposed tariffs, fixing a new effective date of September 27. Originally set for August 1 implementation, the customs duties were on hold while the USTR reviewed more than 1,100 public comments on its proposal.

Key takeaways:

- The U.S. Section 301 tariffs on Chinese imports were postponed as the USTR reviews public comments.

- The Biden Administration seeks to balance clean energy transition, domestic manufacturing, and reduced dependence on China.

- Section 301 tariffs have raised costs for importers and exporters, potentially leading to higher consumer prices in the long run.

- Public comments reflect a mix of support for tariffs to reduce China’s dominance in renewable energy and concerns about their impact on U.S. manufacturers.

- U.S. solar imports have significantly shifted, with Vietnam becoming the top supplier and China’s market share declining sharply.

- Chinese companies are investing in solar production facilities outside China, impacting the U.S. market dynamics.

- There are worries that Chinese companies may circumvent tariffs by using foreign affiliates to import solar products into the U.S.

Weighing tariffs’ costs …

The USTR acknowledges that the protections afforded by Section 301 tariffs come with costs. The USTR’S four-year review summarizes studies of the economic impact of the Trump Administration’s rounds of Chinese import tariffs starting in 2018-2019: In general, higher costs were incurred by industrial importers of intermediate inputs, and by exporters of the products made from these inputs. The higher prices for inputs have been mostly absorbed by the importing and exporting companies, and not consumers – at least until now. That may change over the long term, according to the USTR.

In its public comment outlining the case against the Section 301 tariff increases, the China Chamber of International Commerce argues those price boosts will inevitably be passed on to consumers. In the meantime, the CCOIC says, the higher costs of importing – the direct costs of the tariffs and the added costs of importing from alternative sources – unfairly disadvantage the small and mid-sized importers less able to absorb them than larger corporate enterprises. [This and other comments cited can be accessed at the USTR Comments Portal, Docket ID: USTR-2024-0007.]

… against tariffs’ benefits

As to the benefits gained: the USTR found that the 2018-19 Section 301 tariffs had a positive impact on employment in the protected industries, while U.S. manufacturing employment overall declined fractionally as the higher costs of inputs and China’s retaliatory tariffs took their toll on exports.

Put another way, the Section 301 trade tariffs protected the domestic makers of end products for sale to domestic markets but added to the costs of makers that bought their inputs or sold their products abroad.

This is the gist of public comments supporting Section 301 tariffs on photovoltaic (PV) cells and panels. Most agree with the American Alliance of Solar Manufacturers that higher tariffs are needed to “reduce China’s dominance over renewable energy manufacturing.” But the tariffs should not be applied where they might handicap U.S. producers. Thus, the Alliance endorses excluding from tariffs 19 types of manufacturing equipment needed to ramp up U.S. production and available primarily from China.

Opinions differ on what Chinese products should be excluded and for how long. For instance, NorSun, a Norwegian manufacturer of silicon solar wafers building a factory in Tulsa, asks that the proposed exclusion for key equipment be extended a year to May 31, 2026, “due to the lengthy schedules to build complex manufacturing factories.” Laplace Renewable Energy Technology nominates additional tools and equipment essential to advanced PVC technology. Suniva, which is restarting cell manufacturing in Georgia idled in 2017, reported it had already incurred significant expense from Section 301 tariffs in sourcing equipment available from no source other than China, and would like to see exclusions extended retroactively. The Solar Energy Manufacturers for America (SEMA) Coalition endorsed recommendations to make the exclusions retroactive to January 1, 2023; extend the exclusions to May 31, 2026; and expand the list of inclusions to include some non-core inputs.

It should be noted that the US-EU Solar Manufacturing Committee, representing manufacturers in the U.S., EU, and South Korea, was among those urging the USTR not to exclude any solar manufacturing equipment, while assuring that these products can be supplied by its members.

In its final determination, the USTR has shortened the list of excluded equipment from 19 to 14 and extended the exclusions retroactively to January 1, 2024. It has also proposed modifications of tariff rates on certain tungsten, wafers, and polysilicon tariff lines.

Shape-shifting PV solar supply chains

One indisputable result of the Section 301 trade tariffs on solar imports has been the reshaping of global supply chains – radically and rapidly, though perhaps not always as intended. Here’s an overview of U.S. clean energy trade imports over the last decade:

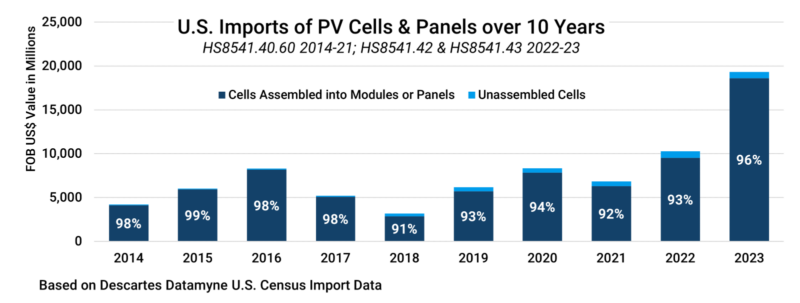

Figure 1 Value of U.S. imports of solar cells & panels 2014 through 2023

Source: Descartes Datamyne

Note that new 6-digit tariff codes were introduced in 2018 and again in 2022. As of 2022, two 6-digit headings denote PV solar cells and panels (HS8541.42 and HS8541.43 respectively). Data prior to 2022 falls under HS8541.40.60, a heading which covers 10-digit codes distinguishing between cells and panels. As the chart shows, solar modules or panels account for most of the value of U.S. clean energy trade.

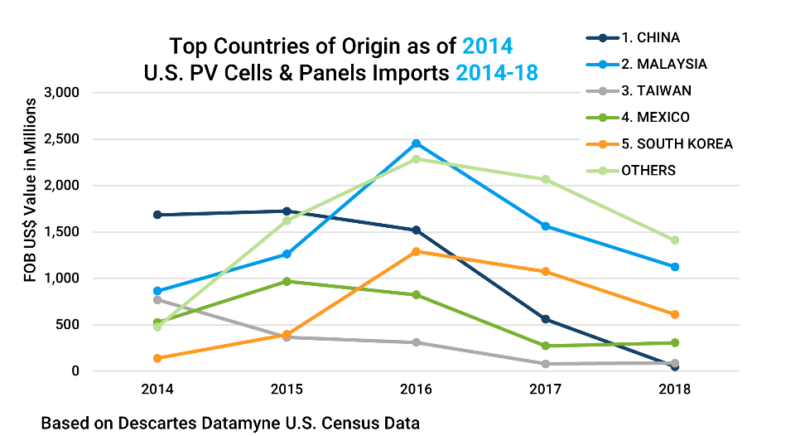

The next three charts capture the shifts in sources since the first antidumping-countervailing duties (AD/CVD) were imposed by the U.S. on solar cells and panels from China at year-end 2012. At the time, China was top-ranked by value country of origin for U.S. solar imports, commanding a 32.4% share, followed by Malaysia (28.6%), and Mexico (9.2%). One year on, China continued to lead with an expanded share of 37.7%, while Taiwan began its descent in the rankings as shown in Figure 2. China followed in 2015, as the U.S. closed a loophole that exempted Chinese solar panels from the tariffs as long as they were assembled with non-Chinese (often Taiwanese) cells.

Figure 2 2014’s top sources for U.S. solar energy imports – 5-year trend

Source: Descartes Datamyne

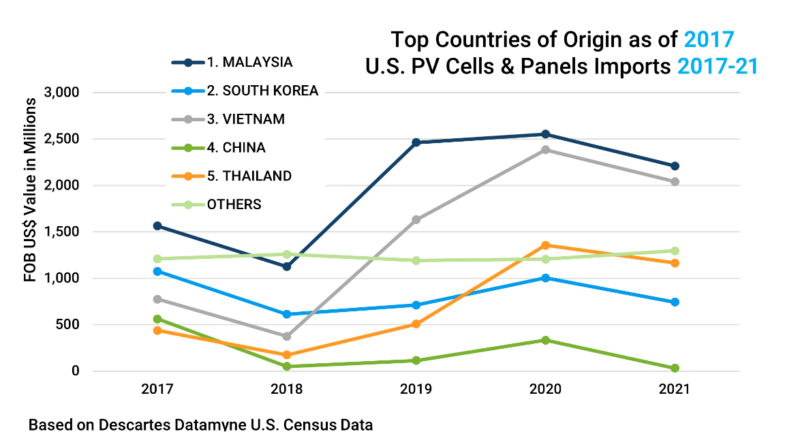

By 2017, the top suppliers of U.S. imported solar panels were led by Malaysia (with a 27.8% share), South Korea (19.1%), and Vietnam (13.8%). Under the weight of AD/CVD tariffs, China had slipped to No. 4 (and would fall still further in the next five years). Surging solar imports had left the U.S. domestic industry reeling: As the USTR noted, one of the two remaining U.S. producers of solar cells and modules declared bankruptcy that year. This time the remedy, announced in February 2018, was “Safeguard Tariffs” under Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974. In June 2019, the USTR excluded bifacial solar panels from the Safeguard Tariffs (the exclusion was subsequently withdrawn, then restored that year), boosting imports from Southeast Asia, as Figure 3 illustrates.

Figure 3 2017’s top sources for U.S. solar energy imports – 5-year trend

Source: Descartes Datamyne

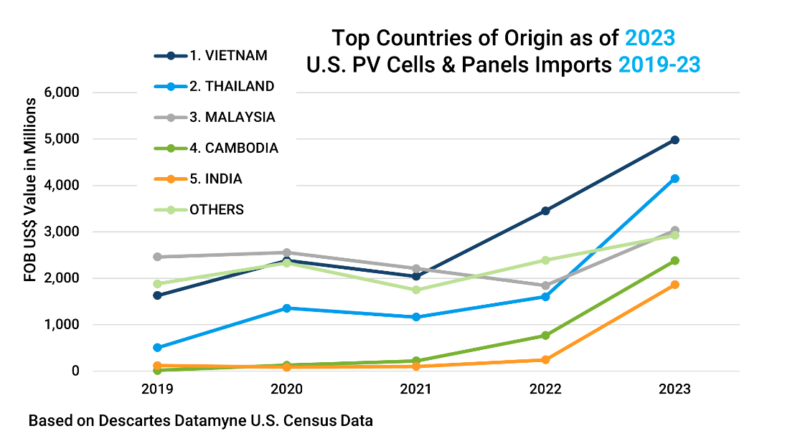

By 2023 Vietnam had vaulted from No. 3 to No. 1, claiming a 25.8% share of this trade, followed by Thailand (21.5%), Malaysia (15.7%), and Cambodia (12.3%). Imports from the four Southeast Asian sources got a boost from President Biden’s June 6, 2022, emergency order to exempt them from any tariffs for two years because of looming solar panel shortages in the U.S. – as Figure 4 indicates.

Figure 4 2023’s top sources for U.S. solar energy imports – 5-year trend

Source: Descartes Datamyne

Meanwhile, erstwhile leader China, ranked No. 17 with share of 0.07% in 2023, appears to have faded as a significant player in this trade.

China steps up investment in extra-national PV solar production

In fact, as China has faded as a direct supplier of solar panels to the U.S., it continues to have a direct impact on the market realities faced by U.S. domestic producers for several reasons.

Begin with the investment China’s solar companies have made in production facilities beyond its borders. Favored destinations for direct investment have been Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand. The latest entrant to the top five COOs for solar imports, Cambodia shipped no solar panels to the U.S. in 2015 through 2018, Descartes Datamyne U.S. Census Data shows. Heng Sokkung, Cambodia’s Secretary of State, reports that 18 of the 21 solar panel factories up and running in his country as of July 2022 are the result of Chinese investments.

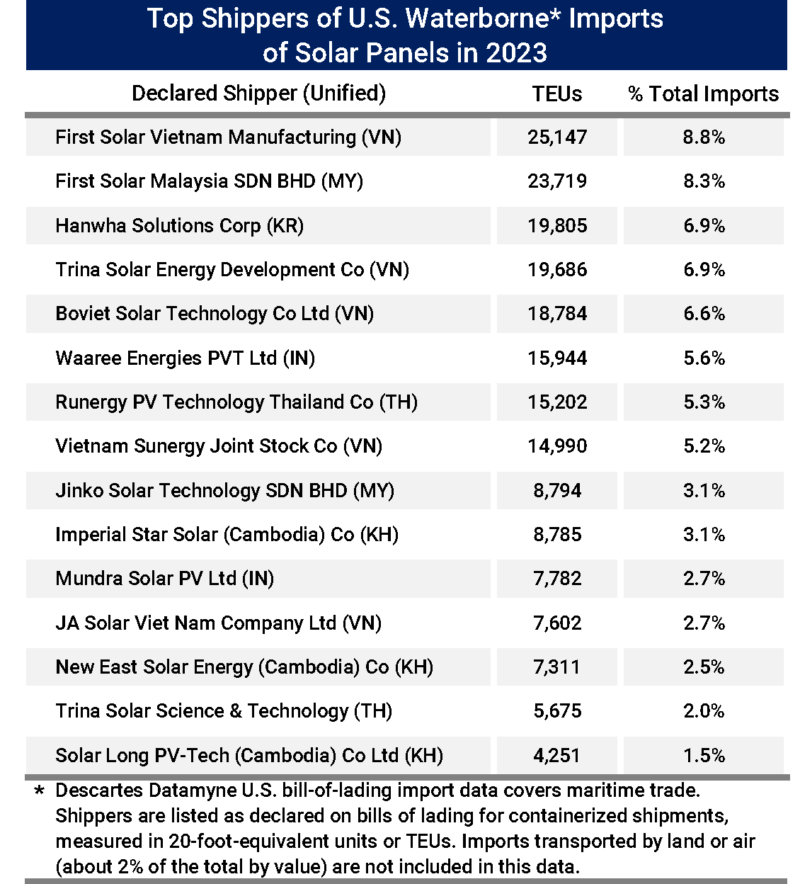

Descartes Datamyne U.S. import bill-of-lading data indicates the extent to which U.S. clean energy trade remains reliant on Chinese company affiliates for solar panels. Here’s a summary of 2023 shippers ranked by volume:

Figure 5 Top suppliers of solar panels to the U.S., ranked by volume, in 2023

Source: Descartes Datamyne

The affiliation of several suppliers is apparent from their names: First Solar is the leading U.S.-based manufacturer of solar panels, while Trina Solar, Runergy, Jinko Solar, and JA Solar are all Chinese solar development companies. Boviet Solar in Vietnam is part of the China’s Boway Group.

That China might use its extra-national partners as “backdoors” around Section 301 tariffs is a recurring concern. In 2022, the USTR reported evidence that some Chinese companies circumvented AD/CVD tariffs by shipping through foreign affiliates. Additional duties were not exacted then because the Biden Administration’s emergency tariff exemption was in effect. This April, U.S. producers represented by the American Alliance for Solar Manufacturing Trade Committee requested a U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) investigation into alleged dumping of PV cells and panels from Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam. A preliminary determination by the USITC is expected in October.

According to an August 2 research note from the Federal Reserve, the rerouting of Chinese goods through other countries to the U.S. to end-run the tariffs has been limited. At the same time, the Fed’s analysis finds that, while the U.S. has made progress in derisking from China, its foreign suppliers have become more reliant on Chinese imports.

The unintended consequences of the Section 301 tariffs appear to be at work. The Section 301 tariffs have encouraged Chinese companies to shift their production abroad and their exports to other markets. The U.S. Section 301 tariff hikes on have resulted in making Chinese goods comparatively less expensive for other countries. Meanwhile, the U.S. has been shifting to suppliers with stronger trade ties with China. In any event, there are few alternative sources for essential inputs to the cell-making and panel-assembly processes. China’s share in all the manufacturing stages of solar panels (such as polysilicon, ingots, wafers, cells and modules) exceeds 80%, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

China doubles down on clean energy exports

With a goal of global leadership in clean energy technologies, China has developed its capacity to produce clean energy products from PV solar panels to electric vehicles well beyond its domestic market’s capacity to absorb them. (The Economist notes Bloombergn estimates that China will be able to turn out enough lithium-ion batteries to supply world-wide demand three times over in 2025.)

Certainly, China appears to be intent on flooding the global market with solar panels, causing a dramatic drop in prices and jeopardizing efforts to build a robust U.S.-based solar manufacturing capability, as the Financial Times reports – even as low prices boost U.S. solar installations. China is making its own trade-off with this strategy. Chinese producers’ prices, which are nearly two-thirds lower than U.S. counterparts’, have helped them win market share, but at the sacrifice of profitability and stock market performance, the Economist reports.

More immediately, the pending Section 301 tariffs appear to have resulted in a fresh surge of U.S. imports of solar panels, as the Descartes Datamyne U.S. Census data, summarized in Figure 6, confirms.

Figure 6 Surge in U.S. Solar Panel Imports ahead of Pending Tariffs

Source: Descartes Datamyne

Alarmed by accelerating imports from China’s Thai and Vietnamese affiliates ahead of impending duties, the American Alliance of Solar Manufacturers on August 15 petitioned Commerce for emergency relief in the form of retroactive tariffs on panels imported since its initial petition in April, as Bloomberg reports.

Objections to the Section 301 tariffs have been raised by clean energy advocates, such as the American Council on Renewable Energy, who fear higher costs will slow installations. U.S. solar manufacturers’ whose supply chains run through Southeast Asian also raise concerns about tariff-driven cost increases in their products. Ironically, as Reuters reports, several of these are new U.S. operations set up by China’s top solar development companies with the support of subsidies under the Inflation Reduction Act.

How Descartes Datamyne Can Help

Descartes Datamyne offers comprehensive trade data and analytics that can empower businesses and policymakers to navigate the complexities of the Section 301 tariffs. Our robust U.S. imports database provides real-time insights into import/export trends, tariff impacts, and supply chain shifts, enabling informed decision-making.

With detailed tracking of U.S. solar panel imports, including country of origin and volume, companies can identify opportunities and potential risks in their supply chains. By leveraging our data, stakeholders can better understand market dynamics, assess the effects of the Section 301 tariffs, and adapt strategies to stay competitive in the evolving clean energy sector. Whether you’re a manufacturer, importer, or policy advocate, Descartes Datamyne equips you with the critical information needed to thrive in a rapidly changing environment.